Member Story: The Shape of Solidarity

/Shannon Corrick

by Shannon Corrick

I come from a union family. My father’s pension kept my widowed mother and me afloat after he died. My uncle voted to strike in 2004, standing shoulder to shoulder with his crew when it mattered most. My grandmother on my dad’s side, though, had a different story. She lost her thumb working in the Bremerton shipyards during the Second World War and was excluded from the union because she was a woman. During that time, manufacturing took advantage of the wartime demand for labor, exploiting women workers without membership and the protections that came with it.

That contradiction runs through labor history and through my family: the same structures that built working-class stability for some of us also profited from leaving others out. And that tension between care and exclusion, solidarity and control, has shaped my entire professional life.

For more than a decade I’ve worked in organized labor, serving, representing, and supporting workers. For another decade, I taught Women’s and Gender Studies, Communication, and Composition & Rhetoric. At Eastern Washington University, I helped the organizing effort to form the United Faculty of Eastern. With UFCW 3000, I became the organizer and helped cannabis workers join a union. My classrooms were full of the same energy and conviction I saw on the picket line: people learning that their voices mattered.

When I wrote my graduate thesis over twenty years ago, I called my approach “maternal methodology.” It was an experiment in what I now recognize as feminist pedagogy; a non-hierarchical model that invited students to become experts in their own learning. My hypothesis was that if we replaced policing with nurturing, if we structured freshman English as a space of care rather than correction, more students would persist through college instead of dropping out. I didn’t have the words for it then, relying instead on what the Brazilian educator Paulo Freire called “education as the practice of freedom.”

At the time, I was also reading bell hooks, Starhawk, Angela Davis, and other thinkers who taught me that love and justice are not opposites—they’re the same discipline, practiced differently in different contexts. I met both bell hooks and Maya Angelou in person. Their words and presence reshaped me. They taught me that power without care corrodes, and care without power collapses.

Those same lessons live in the labor movement.

When I look at unions’ structure of shop stewards, reps, locals, and internationals, I see a living example of feminist democracy. Authority isn’t permanent; it’s contextual. The person with the most experience leads in that moment. Leadership rotates and remains accountable. It’s a system built, at least in theory, on care, consent, and collaboration. It isn’t perfect because no democratic system is, but it’s one of the few institutions in American life where people still practice solidarity as a verb.

In 2021, I was diagnosed with breast cancer. I had surgery, and the long road that follows. Because of my union-negotiated health insurance, cancer cost me $25 out of pocket. My union rep personally sent me flowers after my mastectomy. That wasn’t charity. That was solidarity in action. It was proof that collective bargaining isn’t abstract; it’s embodied. It saves lives.

That experience deepened my conviction that real solidarity looks less like the rigid hierarchies of old-school communism and more like a living, breathing community of care. I’ve often said that communism, in practice, feels like a matriarchal model co-opted and masculinized. A system that tried to harvest the benefits of shared responsibility without surrendering male dominance. But when we remove the hierarchy, when we center the most vulnerable (the children, the disabled, the elderly) and when expertise replaces domination as our organizing principle, we begin to glimpse a structure that feels genuinely feminist and humane.

This isn’t a new idea. Feminist scholars from Nancy Fraser to Silvia Federici have argued that care work and collective labor are two halves of the same struggle. The fight for fair wages is inseparable from the fight to value the unpaid labor that sustains life itself. When unions embrace that understanding, when we fight not just for contracts but for communities, we become something larger than an institution. We become the embodiment of what Angela Davis called “the collective mind of the movement.”

My years teaching and my years in labor are not separate chapters; they’re the same story told in different languages. In both spaces, the goal is to help people find their voice, claim their agency, and recognize their power as interdependent, not individual. Both require listening. Both require courage. Both require faith in the transformative potential of ordinary people.

Now, as I return to teaching through the Labor Education Resource Center, I feel that spark again. The joy of preparation, of dialogue, of building something together. I’d forgotten how good it feels to be intellectually alive, to stand in that space where theory meets practice and the room becomes a workshop for liberation.

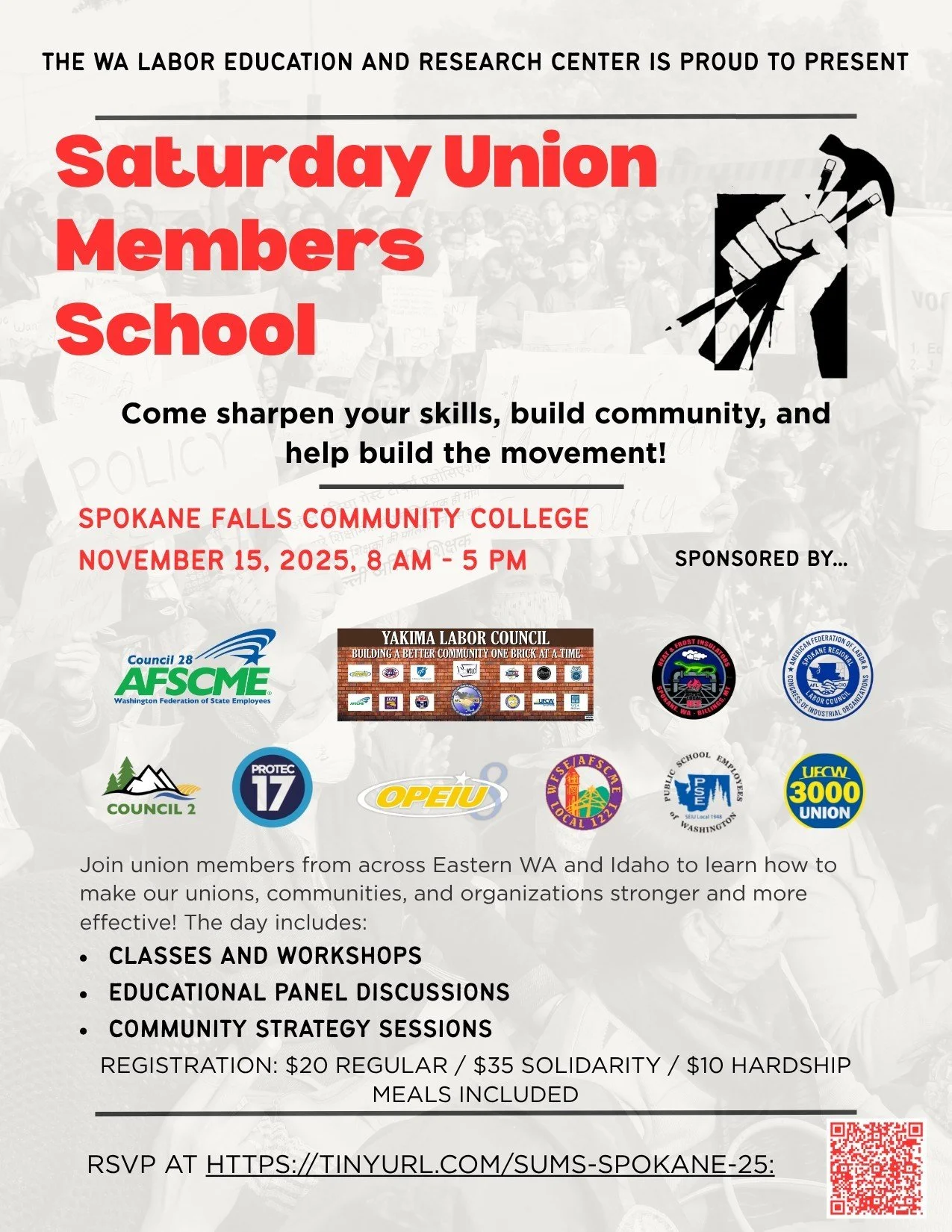

spokane-area members: Power up with saturday union members school on nov 15, 2025.

What I’ve learned over time is that solidarity isn’t just a slogan or a vote. It’s a pedagogy, a way of learning each other into freedom. My grandmother’s missing thumb, my father’s pension, my uncle’s strike vote, the flowers after my surgery, they’re all part of the same lineage. They remind me that labor, at its heart, is a practice of care: care for each other, care for the work, care for the world we’re building together.

When we remember that, when we structure our unions and our classrooms around it, we come closer to the kind of society bell hooks envisioned: one where love is not sentimental but structural, where power is not domination but shared capacity.

That’s the shape of solidarity. It’s not a pyramid; it’s a circle.